The story so far:Russia’s war in Ukraine has entered its third year. What many thought on February 24, 2022 would be a swift Russian military operation against its smaller neighbour has turned out to be the largest land war in Europe since the end of the Second World War. The war has pushed Russia to turn towards Asia and the Global South in general, while the West continues to support Ukraine in its bid to push back and weaken Russia. A vast majority of countries, including India, remain neutral as the violence continues.

Did Vladimir Putin err?

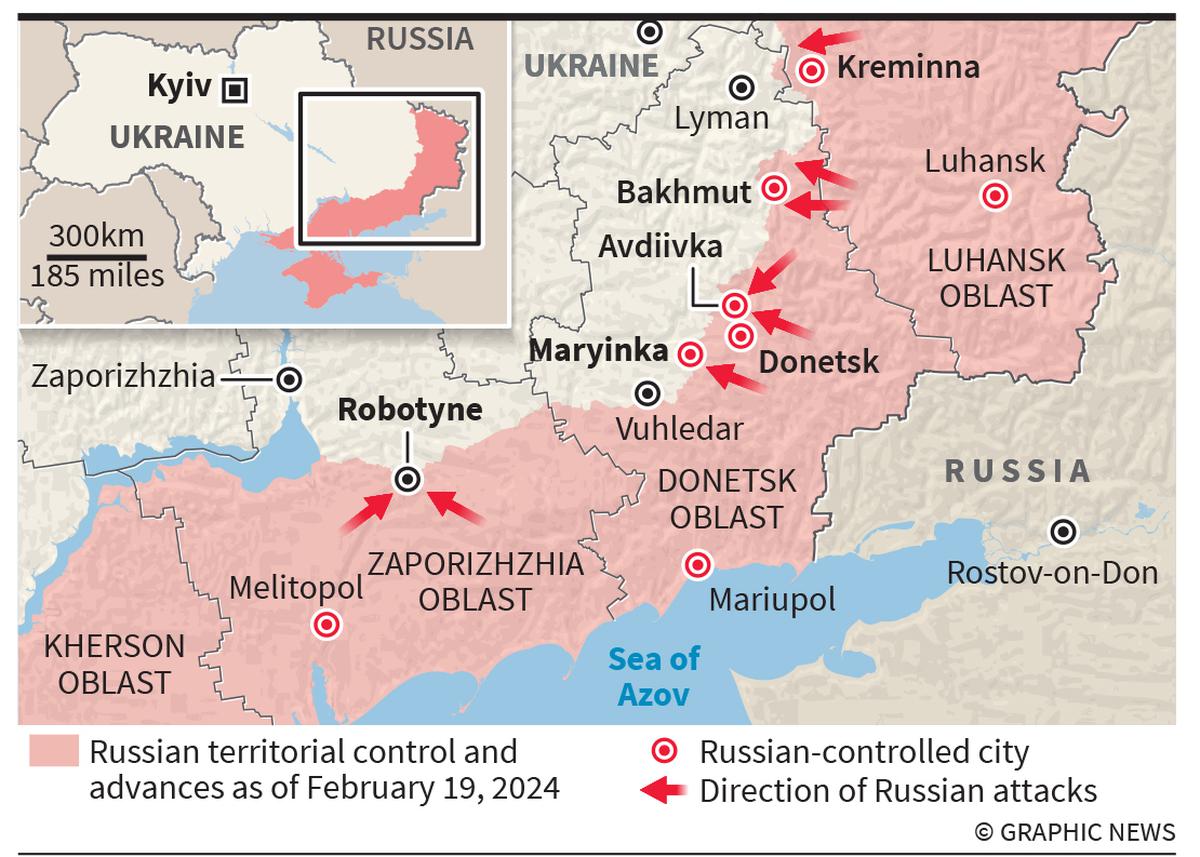

There’s now a consensus among defence experts — as well as reports from leaked western intelligence assessments — that President Vladimir Putin made a grave strategic miscalculation when he ordered the invasion of Europe’s second largest country (after Russia), also a close ally of NATO, with less than 2,00,000 troops. Mr. Putin probably expected a quick victory, like he did in Georgia in 2008 and Crimea in 2014. But as the Russian war machine got stuck in Ukraine, the West moved in with military assistance, training and international mercenaries (what Ukraine calls its “international legion”). After his troops were forced to pull back from Kharkiv in 2022, Mr. Putin immediately ordered a partial mobilisation. Since then, the focus of Russia’s military campaign shifted from all out offence to strengthening the lines of defence with limited offensive battles. When Ukraine was preparing for a major counteroffensive, Russia kept thousands of Ukrainian troops engaged at Bakhmut in Donetsk, while at the same time building defence fortifications along the 1,000-km long frontline. Last May, the Russians took Bakhmut. The battle caused enormous damage to Ukraine and delayed its counteroffensive. By the time Ukraine’s counteroffensive began in June, the Russians were prepared.

In pictures| A look back at the two years of Russia-Ukraine war

Where does the war stand now?

Eight months after Ukraine’s counteroffensive began, it’s now evident that the campaign failed, as admitted by Gen. Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the commander of Ukrainian forces, who was fired by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy earlier this month. Gen. Zaluzhnyi had called for a mass mobilisation, suggesting that Ukraine was facing acute shortage of fighters on the frontline. They lost many of their West-supplied weapons in the counteroffensive and are waiting for fresh supplies, but aid from the U.S. is stuck in Congress amid Republican opposition. On the other side, the Russians are on the offensive. In December, Russia claimed its first victory since the fall of Bakhmut when it captured Maryinka, in Donetsk. Earlier this month, Ukraine was forced to abandon Avdiivka, a strategically important town in Donetsk, after months-long fighting and suffering huge losses. The Russians are now advancing westward in Donetsk and piling up pressure on Ukrainian forces in Krynky, Kherson, in the south.

What is the West’s strategy?

The West had taken a two-fold approach towards Ukraine. One was to provide economic and military assistance to Kyiv to keep the fight against Russia going on; and the second leg was to weaken Russia’s economy and war machine through sanctions. With Ukraine’s failed counteroffensive and a changing political climate in Washington with the prospect of a second Trump presidency looming, the first pillar of this policy faces uncertainty, if not absolute peril. The second pillar, sanctions, has hurt Russia badly. Western officials believe that sanctions have deprived Russia of over $430 billion in revenue it would otherwise have gained since the war began. Europe has also curtailed its energy purchases from Russia with sanctions making it have made it difficult for Moscow to acquire critical technologies, including microchips, which are necessary for its defence industry. But that’s not the whole story.

How have the sanctions affected Russia?

Russia has found several ways to work around sanctions and keep its economy going. When Europe cut energy sales, Russia offered discounted crude oil to big growing economies such as China, India and Brazil. It amassed a ghost fleet of ships to keep sending oil to its new markets without relying on western shipping companies and insurers. It set up shell companies and private corporations operating in its neighbourhood (say Armenia or Turkey) to import dual use technologies which were re-exported to Russia to be used in defence production. China, the world’s second largest economy, ramped up its financial and trade ties with Russia, including the export of dual use technologies. Russia moved away from the dollar to other currencies, mainly the Chinese yuan, for trade, and boosted defence and public spending at home (its defence budget was raised by nearly 70% this year). It also strengthened ties with Iran and North Korea, which were also reeling under American sanctions, and imported weapons from them, ranging from drones to cruise missiles and ammunition.

Two years after the war started, despite sanctions, both Russia’s energy industry and its military industrial complex remain vibrant. Russia earned $15.6 billion from its oil exports alone in January, up from $11.8 billion last summer, according to the International Energy Agency. The Russian Defence Ministry claims that it manufactured 1,530 tanks and 2,518 armoured vehicles in 2023. Western officials had assessed last year, according to a New York Times report, that Russia has the capacity to produce some two million artillery shells a year and that its missile production capacity had surpassed pre-war levels.

How is the war transforming Russia?

It doesn’t mean that everything is going well for Mr. Putin and his compatriots. Since the war began, two countries in its neighbourhood, Sweden and Finland, have joined NATO, expanding the alliance’s border with Russia. Mr. Putin spent years, after coming to power, to build strong economic ties with Europe, which are now in tatters. Russia’s hold on its immediate neighbourhood is also loosening, which was evident in tensions with Armenia and the latter’s decision to freeze participation in the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Russia is also becoming dependent on China, even though the Kremlin is careful not to upset the sensitivity of New Delhi.

Internally, the Russian state is tightening its control over society and is clamping down on any criticism of the war. The Prigozhin rebellion of last year exposed chinks in the armour of the state Mr. Putin has built. The death of Alexei Navalny, the most vocal critic of President Putin in Russia, in a remote Arctic prison on February 16 endorses criticism of the way Russia handles dissent. If post-Soviet Russia appeared to be a “managed democracy”, post-war Russia is sliding into a tightly held authoritarian state.

What does it mean for the world?

The Western strategy of empowering Ukraine through aid and weakening Russia through sanctions doesn’t seem to have worked. The war has also exposed the limits of Western power in a changing world — for sanctions to be effective, the trans-Atlantic alliance now needs the support of other major economies such as China and India. While Russia has constantly found ways to work around sanctions, it has also suffered huge casualties and will have to fight the long term effects of the sanctions. If there is one great power that stays relatively unscathed by this chaos, it is China. When Beijing looks at the conflict, it sees both the West and Russia stuck in Ukraine, forcing the latter to pivot to Asia, redrawing the global balance of power.